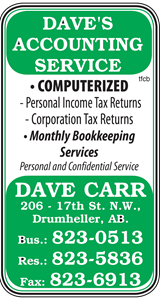

Scott Ouellette tees off at the World Transplant Games in Sweden in 2011. (inset) Ouellette at the Canada Games in 2012 with Leslie Crawford (middle) and Dr. Debra Isaac (right). Both are directors of the Dear Heart Foundation and Dr. Isaac is also one of Ouellette’s transplant cardiologists.

Scott Ouellette is alive today because another person somewhere took the time to make sure their family knew they were an organ donor.

Ouellette is the manager of Acklands Grainger in Drumheller. In 2008, he was 28 and living the typical life of any man his age in Red Deer. He kept relatively active with golf and playing recreational hockey.

He and his girlfriend had just purchased a home.

One night, playing recreational ball hockey, he began having chest pains, sweating, and having a hard time breathing. Ouellette likes to push the boundaries and he played through the pain and finished up the game, despite his friends' and girlfriend’s advice.

At 2 a.m., he couldn’t take the pain and was sent by ambulance to the Red Deer Hospital. Quickly he learned he was having a massive heart attack and was airlifted by STARS to the Foothills Hospital in Calgary. Ouellette had two blocked arteries. Doctors put a stent in one artery and a balloon in the other. He woke up three days later on a ventricular assist device.

“This (ventricular assist devise) is basically a pump running the left side of my heart. The heart attack was so bad it killed all my aortic muscles, so my aortic valve opened once every eight beats... not enough to survive,” said Ouellette.

This is shocking to anyone, let alone a 28-year-old man.

“I was told there is a 99 per cent chance I am going to need a new heart,” he said. “It was a wake up call. I had no previous history, and no idea this could happen… all they said was there was no way at this age that I should have two blocked arteries.”

His heart attack was on April 23. By the end of June, he was again pushing boundaries, golfing, using his ventricular assist device.

Ouellette waited 113 days and received the call for a transplant.

“I got the call on August 15 at 2:30 in the morning and I was in surgery at 4:30 that afternoon,” he said.

After a 12-hour surgery, the heart took. In two months, he was golfing and back at work, and in five months, he was back playing hockey.

“I’m kind of stupid that way, he laughs, “I push the envelope.”

On the one-year anniversary of his transplant, he and his girlfriend got married.

He has nothing but praise for all the support he received through this ordeal. Acklands was supportive by giving him the time he needed to recover, his parents were still living in Calgary during his recovery, which was a great support, and the medical community from beginning to end was incredibly professional and supportive.

As expected, he had a whole gamut of emotions through this process. At one of the low times, his nurse in the hospital told him about the world transplant games.

“She said, ‘do you know there is an Olympics for transplant people?… I’ll give you a contact and you can find out about it,’” Ouellette told The Mail.

Ouellette's goal was to recover and make it to the 2011 games in Sweden. He achieved this and his wife and parents all came to see him compete.

"There were 1,500 athletes from 51 different countries, all with various transplants,” he said.

In 2012, he competed in the Canada Games in Calgary and earned three golds and a bronze medal.

Ouellette's ordeal is something he carries every day, but at the same time it has never limited him. He has kept a number of items, including his original ventricular assist device. He sees the scars every day, and he will be on anti-rejection drugs for the rest of his life. He has also received correspondence from the family of his heart donor and learned her name was Kimberly.

‘It is a constant reminder,” he said. “Each day I wake up is a gift from her. She is the reason I’m alive.”

He is fine with the reminders and he wants to share his story to help raise awareness. He has become an active member with the Dear Heart Foundation, which raises funds to support enriching the lives of cardiac transplant patients. He has volunteered speaking at events and even meet with transplant patients to help them through the process.

One of the main messages Ouellette wants to get out is to make sure you do more than simply sign your organ donor card. He explains that organ donations will not happen without consent from the family of the person, even if the card is signed.

“The most important thing people can do is actually talk to their family and let them know their wishes. Most of the time doctors come to ask about organ donation, it is not long after you are told your loved one is not going to make it,” he said. “A lot of people think they want to harvest their body and not save them, but that is completely not the case. They do everything they can to save a life, before they even consider donations.”

“I tell people at Christmas or Thanksgiving, bring it up.”

A common reason for not donating he hears is “they wouldn’t want my organs.”

“The one thing we say is let the doctor decide. You don’t know what shape your organs are in so let the doctor decide. There might be someone who gets your organ, or else dies,” said Ouellette.

“People look at me and can’t tell I had a heart transplant unless I tell them. I always tell them because the only way we are going to get more organs for more people to be saved is through awareness.”